This week, in The New York Times’ Room for Debate, I was involved in a discussion on the brewing war among environmentalists over building large power plants on sensitive land — specifically, in this case, a solar thermal power plant in the Mojave desert. “Green Civil War: Projects vs. Preservation” saw contributions from:

- Randy Udall, energy analyst

- Vaclav Smil, professor, University of Manitoba

- Daniel M. Kammen, professor of energy, U.C. Berkeley

- Ileene Anderson, Center for Biological Diversity

- Winona LaDuke, Honor the Earth Fund

And me! Turns out it’s very difficult to make a point in 300 words, at least for me, so I’m reposting my contribution below and will add a few additional comments at the bottom.

——

Many folks are conflicted over the seeming clash between conserving America’s remaining wild landscapes and expanding clean energy supplies. What to do?

To begin with, it seems prudent to postpone the conflict as long as possible, by making every effort to satisfy new energy demand with low-carbon resources on land that’s already developed. Senator Feinstein has gestured in that direction, but neither California or any other state has ever offered serious, sustained support to what’s loosely called distributed energy — energy generated, stored and managed at the local level.

The U.S. power industry has always had a fondness for gigantism: huge plants, remotely located, generating electricity that’s sold cheaply and used profligately. Wind farms on the Plains and solar plants in the Southwest desert, connected to cities by expensive new transmission lines, fit the familiar model. Regulations provide incentives for this development, which utilities know how to manage, and which politicians understand.

Yet the land and water problems facing solar plants should be a reminder that all large new industrial projects impose social costs. Perhaps it’s time to take distributed energy seriously.

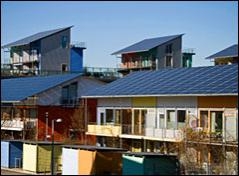

What would a new model look like? Solar panels over every parking lot, brownfield, warehouse, and residential roof. Small-scale wind turbines on every bridge, microhydro in every stream and river, advanced geothermal in every back yard, waste heat capture on every industrial plant. Batteries that store power to be used or sold when it’s worth most. An IT-infused grid that can manage complexity; devices that display real-time use and price information; variable power pricing. Every building sealed and weatherized, every appliance and electric car net-connected.

In such a system, it’s not just energy that’s distributed, it’s social and economic power. The result is more democratic and resilient (though such benefits rarely find their way into conventional price comparisons). If “consumers” become producers, managers, and innovators, perhaps the desert tortoise and the world can be saved.

——

A couple of ideas get tossed in here that deserve more mulling.

First, “regulations provide incentives for this development.” Tomes could be written on how utility and power regulations encourage investment in large, remote power plants. Sean Casten is probably writing such a tome right now! The situation differs somewhat between the remaining regulated monopoly utilities and the ones that have been deregulated and/or “decoupled,” like those in California. But even the most enlightened utilities still tend to view distributed energy as a kind of curio, small beans done as much for PR purposes as for serious power.

Part of the difficulty is that that utility regulations are mind-numbingly complex; part of it is that utilities have 50 years of deeply entrenched habits, models, and culture (in which innovation doesn’t play much of a role). But that’s the tip of the iceberg. As the second-to-last paragraph indicates, distributed energy requires not just different generation technology, it requires that cities be made into coherent quasi-organisms, that generation, distribution, storage, transportation, and administration systems be coordinated. Pushing all those systems forward together is a daunting task that will require, at least in the first few instances, a strong dose of central planning, to which Americans are (purportedly) averse.

Third, the last paragraph is something that’s been an interest of mine for a long while: how will distributing the ability to generate, manage, and store power affect social dynamics? What will it look like when communities are more self-sufficient? What kind of innovations will spring up when everyone has access to the levers of energy, the way the internet gave everyone access to information infrastructure? What kind of lives will people live when their energy and gas bills are radically reduced or even eliminated? This is heady futurist sort of stuff, too much to get into in this post, but I suspect the changes will be far more sweeping than anyone can anticipate.

Which leads to a final point: cost comparisons between central-plant power and distributed power are woefully inadequate, typically focusing in on price-per-kWh. Of course rooftop solar fails by that comparison. But what happens when you factor in the saved cost of transmission lines that don’t have to be built? What happens when you factor in the efficiency gains made possible by smart appliances, smart vehicles, and smart grids? What happens when you factor in the fact that money spent on these systems will circulate almost entirely within a community rather than leaving it? What happens when you factor in energy independence, resilience, innovation, jobs?

There are “system of systems” benefits around distributed energy that we can’t yet predict, much yet place a dollar value on. As in so many areas, the question should not be how to save pennies, but how to construct the kind of lives, the kind of society, that reflects our highest aspirations.